The ‘Crit Day’ Study

Yadid

Ayzenberg and Brian D. Mayton

Abstract. We set out to characterize skin

conductance changes as a response to public speaking. A group of 11 graduate

students participated in the study. These students were presenting their thesis

proposals to the faculty and other graduate students on a given day. Each

participant was given two wristband sensors. Each of the wristbands measured electrodermal activity, skin temperature and 3-axis accelerometery.

The participants were required to wear the sensors for 72 hours. In

addition, they were required to submit daily surveys at the end of each day.

The presentations were videotaped.

1.

Introduction

Public speaking

is often associated with high levels of stress and anxiety. Many individuals

fear being in the spotlight, being the center of attention, and the possibility

of standing on stage and forgetting what they meant to say. Additional elements

that may add to the anxiety are the possibility of being asked questions that

they are not prepared to answer. We set out to characterize the skin

conductance changes related to public speaking. Would it be possible to find a

correlation between speakers perceived stress levels and their physiological

response? Were the levels of stress highest before, during or after a talk? Were

the physiological responses of individuals that perceived themselves as very

stressed higher than the ones of those that perceived themselves as calm?

To gain insight

into the answers to these questions, we conducted a study and collected a

dataset including electrodermal activity (EDA) and survey

responses from 11 participants for several days around a stressful public

speaking event. In contrast to most

studies concerned with EDA data, we also collected this data from both wrists

for the duration of the study in an attempt to better understand what might

cause an asymmetric EDA response.

This paper is

organized as follows. Section 2 reviews previous studies on the subject of this

work. Section 3 provides details about the experiment. Section 4 presents the resulting

data set. Section 5 provides results and analysis.

2. Previous Work

It is possible

to measure changes in stress level by using electro dermal activity sensors. Our

“fight-or-flight” response that is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system

is heightened under stressful situations. The sub-dermal sweat glands’ activity,

which is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), can be measured using

biosensors that are placed on the wrist and measure skin conductivity. Boucsein showed that skin conductance is highly correlated

to changes in sweat gland activity. Work done by Setz

et al. showed that it is possible to distinguish between cognitive load and

stress in electrodermal activity. By using EDA peak height and the instantaneous peak rate it is possible

to determine the stress level of a person.

Dimberg et al. found that subjects that possessed a public speaking

fear reacted with increased skin conductance activity when exposed to social

stimuli compared to low-fear subjects.

3. Experiment

Each year, the

MIT Media Lab organizes an event in which second year master's students present

their thesis proposal to all of faculty, students, and researchers. Each

proposal is evaluated in terms of depth, originality, and contribution. The

purpose of these presentations is twofold. The first is that the student will

receive constructive feedback on the proposed work. The second is that it compels the

students to spend time to explore possible research topics while constraining

their schedule. All master’s students are required to participate in a thesis

preparation seminar that will aid them in solidifying their ideas. At the

beginning of this seminar, the students are told of the importance of their

‘Crit Day’ performance that will be a factor that weighs

heavily in their Ph.D. application. Naturally, this adds significant

levels of stress to the students who realize that this speaking event may

determine the future of their academic career.

We decided that ‘Crit

Day’ was a valuable opportunity to measure the physiological effects of public

speaking.

3.1. Study Design

We recruited 11

graduate students, 8 males and 3 females, who were designated to present on ‘Crit

Day’. The youngest was aged 23, the oldest was aged 27 and the mean age was

24.6 (SD=1.2). The students would receive compensation in return for their participation

in the study. We made sure beforehand that none of the participants were

taking medication that could potentially have an arousing or calming affect, or

ADHD medication.

Before the study began, we asked the participants to report

their perceived level of stress during the last month. We used the Perceived

Stress Scale (PSS) as defined by Cohen et al., which is the most widely used

psychological instrument for measuring the perception of stress.

It is a measure of the degree to which circumstances in

one’s life are considered as stressful.

Items were designed to determine how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and

overloaded subjects find their lives to be.

During the three days of the study, we requested the

participants to report their daily perceived stress

levels at the end of each day. We

used the Daily Stress Inventory (DSI) as defined by Brantley et al., which

is a psychometrically sound self-report instrument for the daily assessment of

the sources and the individualized effect of relatively minor stressful events.

It was designed to evaluate causes of stress that are not typically evaluated

by major life-event scales. We add 4 additional questions to the standard DSI

survey:

1.

If something that was unexpected or caused you a great deal of stress, please

note the approximate time and duration of the event.

2.

On a scale of 0=time seemed to take forever, to 4=time

seemed to fly by, how would you say your day felt?

3.

On a scale of 0=felt poorly prepared to 4=felt very

prepared, how well prepared do you feel you were for today's events?

4.

This question mostly applies to ‘Crit Day’ (Nov 14): On a scale of 0=unfair to 4=fair, in your opinion, how fair were the

questions you were asked today?

The goal of question number 1 was to collect data that would

be correlated to changes of the participants skin conductance. We hypothesized

that unexpected events would cause a notable increase in skin conductance

immediately following the event. We also collected similar data by performing

exit interviews upon the completion of the study. However, since some time had

passed from the occurrence of the events to the time of the interview, the

results of these interviews may be biased.

We asked question

2 in order to find whether perceived stress had an impact on the perception of

time duration. We hypothesized that the stringent deadline and sense of urgency

would shorten the perceived duration of time, and that a day after the

presentation, time would be perceived as having a longer duration.

Question 3 was

asked in order to asses if the participants felt that

they were well prepared. We hypothesized that well prepared participant would

have a lower level of perceived stress and that this would

also be evident in their skin conductance.

We asked

question 4 to assess whether the participant felt in control during the

presentation and whether they thought that they were asked fair questions. We

hypothesized that during the question phase, participants who believed that

they were asked “unfair” question would exhibit this physiologically as well.

3.2. Data Collection.

We collected the

following data during the study:

1.

Skin

conductance, skin temperature, and 3-axis accelerometer – we used the Affectiva QTM wristband sensor. The data was

recorded at a sampling rate of 8 Hz, and was recorded using dry Ag-AgCl electrodes. Each participant received a pair of

sensors, one for each wrist, so we could collect bi-lateral data. Each sensor

had a label that was used to note the participant's id and whether the sensor

was to be placed on the left or right wrist. The participants were asked to

wear the sensors for 72 hours starting on the morning of the day before their

presentation.

2.

Self-report

measures – each participant was asked to fill in a PSS survey 2 days

prior to the start of the study. During the study, participants were required

to fill in a DSI survey at the end of each day.

3.

In

addition, we interviewed each participant a few days after the end of the

measurements. During those interviews, we asked the participants to describe

their experiences during the 72 hours. We asked them to note any unexpected

events or events that caused them a great deal of anxiety or emotional strain.

4.

Video

– during the presentations we recorded a video of the participants. In

some cases, we also recorded some of the participant's post-presentation

question sessions.

3.2.2 IT Infrastructure and tools

For participant

registration and conducting the surveys, we built custom Python-based web

software that ran on a server in the lab. The participants could access the

surveys by using a web browser from any location. The tool presented the surveys to the

participants and collected their responses.

A MySQL server

was used to store the survey responses. At the end of the study

we exported all the results from the database into an Excel sheet.

The Q sensor

data was downloaded from each unit and stored in a dedicated server, along with

the survey responses and the video files.

For the signal processing we used MATLAB. We built a Python tool to convert

all of the Q sensor data into MATLAB file format and filter out noise.

We also used a

tool written in Processing by Miriam Zisook that

enabled us to rapidly detect cases of asymmetry.

3.2.1 Privacy Measures

In order to

protect the privacy of the participants, several measures were put in place.

When the participants logged into the web system for the first time, they were

randomly allocated a 5-digit PIN number. They were asked to use this number

every time they logged into the system. In addition, they were asked to write

this number on the labels of the sensors that they were given. This enabled us

to correlate between the subjects sensor reading and their self-reports.

Results and Discussion

We have

collected the following data set:

|

PSS |

11

participants (all) |

|

DSI |

Š

7

recipients filled in all surveys Š

3

participants filled in the first 2 DSI surveys but not the 3rd one

Š

1 participant

did not fill in any of the DSI surveys |

|

Video

and audio during presentation |

10

participants |

|

Interviews |

11

participants (all) |

We calculated

a PSS score per participant. The score is obtained by reversing the responses

of the negatively stated items (e.g., 0 = 4, 1 = 3, 2 = 2, 3 = 1 & 4 = 0)

to the four positively stated items (items 4, 5, 7, & 8) and then summing

across all scale items. This score represented the perceived level of stress

during the last month. The average PSS that was collected for a large

population was 12.1 (SD=5.9) for males and 13.7 (SD=6.6) for females.

We calculated DSI

scores for each participant. Three daily scores are derived for each

individual: (1) the number of events that are endorsed as having occurred (Freq) (2) the sum of the total of the impact rating of

these events (Sum), and (3) the average impact rating of the events (sum

divided by the number of events) (Avg).

The table

below shows the PSS and DSI scores for each participant.

|

Day 1 |

Day 2 |

Day 3 |

||||||||

|

PIN |

PSS Sums |

Freq |

Sums |

Avg |

Freq |

Sum |

Avg |

Freq |

Sum |

Avg |

|

54604 |

25 |

16 |

50 |

3.125 |

21 |

45 |

2.143 |

|||

|

75049 |

22 |

14 |

62 |

4.429 |

20 |

67 |

3.350 |

17 |

34 |

2.000 |

|

34600 |

21 |

25 |

80 |

3.200 |

29 |

122 |

4.207 |

|||

|

05972 |

19 |

15 |

46 |

3.067 |

9 |

25 |

2.778 |

11 |

34 |

3.091 |

|

18372 |

17 |

13 |

31 |

2.385 |

17 |

55 |

3.235 |

15 |

50 |

3.333 |

|

57607 |

17 |

19 |

73 |

3.842 |

14 |

48 |

3.429 |

|||

|

41965 |

10 |

31 |

51 |

1.645 |

23 |

47 |

2.043 |

21 |

63 |

3.000 |

|

36237 |

9 |

13 |

63 |

4.846 |

17 |

55 |

3.235 |

4 |

9 |

2.250 |

|

13113 |

9 |

16 |

28 |

1.750 |

16 |

29 |

1.813 |

16 |

23 |

1.438 |

|

20052 |

8 |

10 |

26 |

2.600 |

8 |

16 |

2.000 |

0 |

0 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 1 PSS and DSI scores

The first

result is that according to the DSI the mean perceived stress across all participants

was highest on the night before ‘Crit Day’ (3.09) and lowest on the night of

the day after ‘Crit Day’ (2.16). On the night of ‘Crit Day’

the perceived stress was in between the two (3.09). The average DSI measured

for a large population in Cohen’s was 2.36 (SD=0.82) for males and 2.68 for

females (SD=0.97)

We assumed

that there should be a correlation between the PSS and the first DSI as they

were submitted within the same time frame. Initially we found that the

correlation between them was 0.3122, which was statistically not significant.

After viewing the plot we noticed that a single

subject was an outlier. Further investigation reveled that the participant had a argument with his partner just before filling the survey.

We suspected this resulted in a biased score. After removing this subject we found that the correlation between the PSS and

first DSI was 0.71, which was statistically significant (p<0.05).

The DSI also

revealed that participants perceived time as passing quickly the day before

‘Crit Day’ (mean = 2.4, SD = 1.5), and passing slower during ‘Crit Day’ (mean =

2.33, mean = 1.21), and yet slower the day after (mean = 1.83, SD = 1.17).

We also found

that most participants felt that the questions they were asked were fair (mean

= 3.8, SD = 0.42).

Initially,

after viewing the EDA signals we found that some of the samples were extremely

noisy. We estimate that the reason for this is loose contact between the sensor

and the skin. We applied an infinite impulse response low pass filter

(exponential smoothing) with different coefficients for rising signals and

falling signals (alpha rise = 0.5, alpha fall = 0.95). This filter is an attempt to reduce

artifacts where the signal briefly but sharply drops due to poor contact with

the skin, which appeared in several subjects' data. We implemented this filter

in Python.

The first

result that arose from analyzing the EDA signals was that there is a notable

difference within each subject between the presentation and the questions

phase. In the question phase, the EDA level was higher, and there were more

peaks per second. This is true

across all participants. We conclude that either the fear of being asked a

difficult question and evaluated by others, or just being

asked a question results in a heightened physiological response

|

|

|

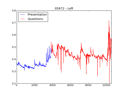

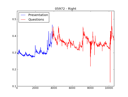

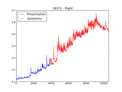

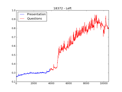

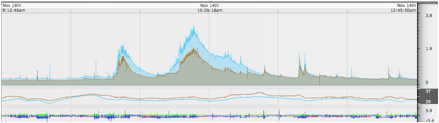

Above can be seen

the left and right EDA signals for two subjects. The EDA during the

presentation is colored in blue, and the EDA during the question phase is

colored in red.

We analyzed all

of the EDA signals for asymmetry. 2 participants out

of 11 exhibited temporary asymmetry in their EDA. There was no correlation

between perceived stress ratings (on DSI and PSS) and asymmetry in EDA. The

snapshot below shows asymmetry that begins just prior to the participant’s

presentation and lasts throughout.

Figure 1 EDA Asymmetry (18372)

during presentation

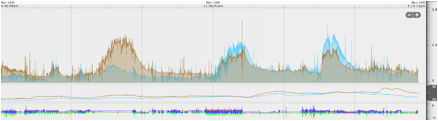

The second EDA

signal also shows asymmetry, as the participant is about to start his

presentation.

Figure 2 EDA Asymmetry (57607)

during presentation

Finally, we tried to count peaks and correlate them with the percieved

stress levels. However, we could not find any significant results. We suspect that our facility for

counting peaks (the findpeaks function in MATLAB's

signal processing toolkit) is confounded by noise in the data from poor contact

with the skin, which varies greatly from participant to participant and, to a

lesser extent, over the course of the day (perhaps due to participants

re-adjusting the fit of the wristband.)

A more careful definition of what constitutes a 'peak' feature in EDA

data and is more robust to noise may yield better results.

|

PIN |

13 Nov Left |

13 Nov

Right |

14 Nov

Left |

14 Nov

Right |

15 Nov Left |

15 Nov Right |

|

5972 |

0.108931 |

0.042647 |

0.097395 |

0.091768 |

0.105573 |

0.091005 |

|

13113 |

0.006115 |

0.016222 |

0.115815 |

0.034953 |

0.112331 |

0.029933 |

|

18372 |

0.016222 |

0.00873 |

0.002861 |

0.031462 |

0.014959 |

0.055563 |

|

20052 |

0.09649 |

0.120339 |

0.013636 |

0.018172 |

||

|

34600 |

0.038732 |

0.245188 |

0.069173 |

0.106703 |

0.218192 |

0.086264 |

|

36237 |

0.036325 |

0.013221 |

0.015145 |

0.00938 |

0.033767 |

0.028134 |

|

41965 |

0.239856 |

0.206557 |

0.403685 |

0.236872 |

0.048534 |

0.032602 |

|

54604 |

2.868826 |

0.163433 |

0.010651 |

0.008393 |

0.562887 |

0.40959 |

|

57607 |

0.140879 |

0.238506 |

0.167272 |

0.438723 |

0.083897 |

0.124151 |

|

75049 |

0.119898 |

0.070873 |

0.269948 |

0.485653 |

0.129117 |

|

|

91405 |

0.113824 |

0.110514 |

0.125519 |

0.100129 |

0.148339 |

0.545966 |

|

Mean |

0.344190727 |

0.112384545 |

0.1021152 |

0.122409364 |

0.1814132 |

0.1532325 |

Table 2

Number of Peaks per Minute using findpeaks and

threshold of 0.001

Conclusion

We have

collected a large dataset, consisting of bilateral EDA data, initial Perceived

Stress Scale (PSS) responses, and daily Daily Stress

Inventory (DSI) survey responses.

Preliminary analysis shows some patterns that we expected, such as

greater activation during Q&A after the presentation (which cannot be

rehearsed) and less during the presentation (which participants likely

rehearsed several times and felt prepared.) The dataset also contains several events

where the participants' EDA is asymmetric, some of which we have associated

with participants' descriptions of events at those times.

The preliminary

analysis that we have done merely scratches the surface. We plan to continue investigating and to

make the de-identified data available to other researchers for further study.

References

Boucsein, W.: Electrodermal

Activity. Plenum Press, New York (1992)

Brantley P.J.,

Waggoner C.D., Jones G.N., Rappaport N.B.: A daily stress inventory: Development,

reliability, and validity. J Behav Med;10:61–731, (1987)

Cacioppo, J.T., Tassinary,

L.G., Berntson, G.G.: Handbook of Psychophysiology.

Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge (2000)

Cohen, S; Kamarck T, Mermelstein .: "A global measure of perceived stress". Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24 (4): 385–396.

PMID 6668417, R (December 1983)

Cohen, S. and

Williamson, G.: Perceived Stress in

a Probability Sample of the United States, The Social Psychology of Health, Newbury

Park, CA: Sage (1988)

Dimberg, U., Fredrikson,

M. and Lundquist, O.: Autonomic reactions to social and neutral stimuli in

subjects high and low in public speaking fear, Journal Biological Psychology,

Volume 23(3), p223 (1986).

Lykken, D.T., Venables,

P.H.: Direct measurement of skin conductance: A proposal

for standarization.

Psychophysiology 8(5), 656–672 (1971)

Mundy-Castle,

A.C., McKiever, B.L.: The psychophysiological

signiřcance of the

galvanic skin response. Experimental Psychology

46(1), 15–24 (1953)

Poh, M., Swenson, N., Picard, R.: A wearable

sensor for unobtrusive, long-term

assessment of electrodermal

activity. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57(5), 1243–1252 (2010)

Setz, C., Arnrich,

B., Schumm, J., La Marca,

R., Troster, G., Ehlert, U.: Discriminating stress from cognitive load using a

wearable eda device. IEEE Transactions on Information

Technology in Biomedicine 14(2), 410–417 (2010)