Background

Design Process and Timeline

Our group was drawn together under the topics of symmetric learning and the developing world. After a painful separation from our friends, the missionary zebras, we resolved to address Ethan’s stated goal of the possibility of a partnership between the Media Lab and the Innovation Hub (iHub) for our project.

Our project was driven by the five original questions posed by Ethan:

-

How do we learn symmetrically?

-

How do we find the right peers?

-

How do we mutually coach?

-

How do we avoid the missionary stance?

-

How do we establish peers without co-presence?

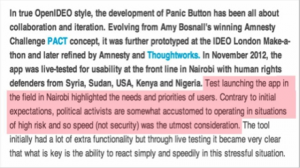

In order to learn more about our future partners and to think about how to proceed, we first learned as much as we could about the iHub from their website, featured events, profiled individuals, and blogs online. We also did some background research about what was being done in the online collaboration space by investigating the existing technological platforms and theories. Obviously, on the ground ethnography and relationship-building in person would have been highly desirable, but we quickly made friends with a limitation that will return again and again throughout this process.

Once we were moving along and felt we were on the right path, we elected to take a two-pronged approach. On the first prong was trying to build a relationship with the iHub as carefully but deliberately as possible—we knew the process would take time, so we got started as soon as we could. We reached out, via Ethan, to Jessica Colaço, a founding member of the iHub and one of the premier researchers in Kenya to learn more about the iHub and discuss the idea of a partnership. Our first call with Jessica was extremely valuable. She was able to give us a lot of insight into the iHub that we could not gather from the static words/images presented online. She walked the computer around her office to give us a sense of the physical space and “vibe” of her office. She gave us her opinion about the real needs of the iHub so we could check our assumptions She warned against demos, and implied co-location as a goal for this collaboration. She identified mentorship and ownership within the community as the most pressing needs.

At the same time, our second prong was to develop the “How Might We”s and try to really develop the technology we were going to use as a shared space and basis for collaboration with the iHub.

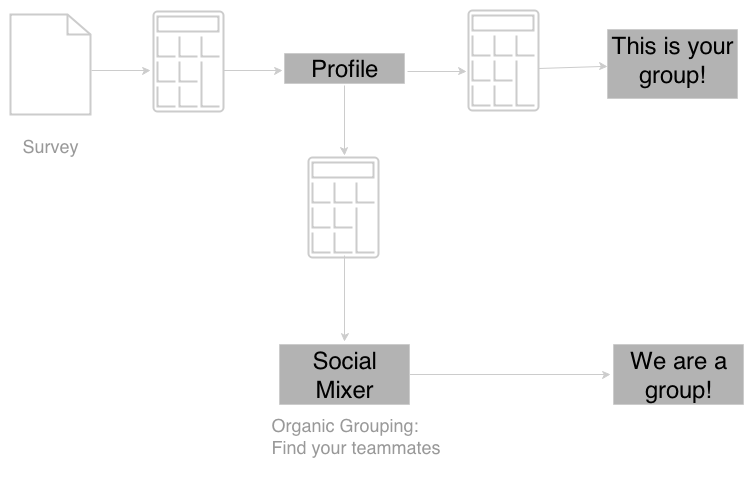

Absent any on-the-ground ethnography, we performed “collaboration case studies” to walk through IDEO’s “AEIOU” process of how people in each of our fields collaborate (teachers, researchers, open source software developers, and MIT students). While none of these groups were the iHub exactly, they were all groups with some structural and aspirational constraints and interests We highlighted similarities and differences across our four groups and tried to work out some analogies that unified these groups. After pushing things to a matrix and further refining, we settled on the “How Might We”s at right. We knew also that we wanted to pursue them with the design principles of co-design, inclusivity, and symmetric learning in mind.

Our answers, after deliberation and checking in with Ethan, were that a combination of shared projects and a place that facilitated less-focused and unified sharing (of cultural knowledge, personal inspiration, appealing future projects etc.) would be a recipe for success. As we worked on these ideas though, dissatisfaction and discomfort crept in – how could we develop this platform all on our own and be true to our design principles? We pivoted to figure out how, without co-location, we could grow the relationship and the culture. Ultimately, we opted to create a mailing list like some ones that are beloved in our communities – the Tufts Fletcher School social list and the Media Lab’s Awesome list. We determined to host the list like a party, trying to imagine the events, sharing and contributions that could facilitate the organic connections necessary to develop new and interesting projects between the organizations while staying true to our design principles.

Our next step was to arrange a call with Jessica and to exhort her to bring more members of the iHub staff along. The call was scheduled early in Boston, but things got off to a late start. The better part of the time was spent on personal introductions, leaving only a small window to briefly float the mailing list idea. We needed to rush to class, so we really didn’t have any time to get much of a reaction. Simultaneously, the Google hangout technology was glitchy, further straining the connection. On the plus side, when we debriefed, we agreed there was a feeling of wanting more, a mixture of hope and disappointment.

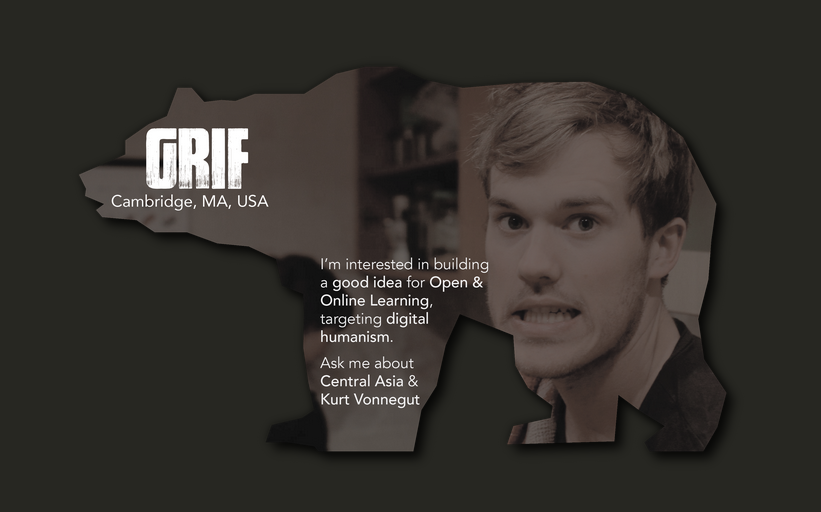

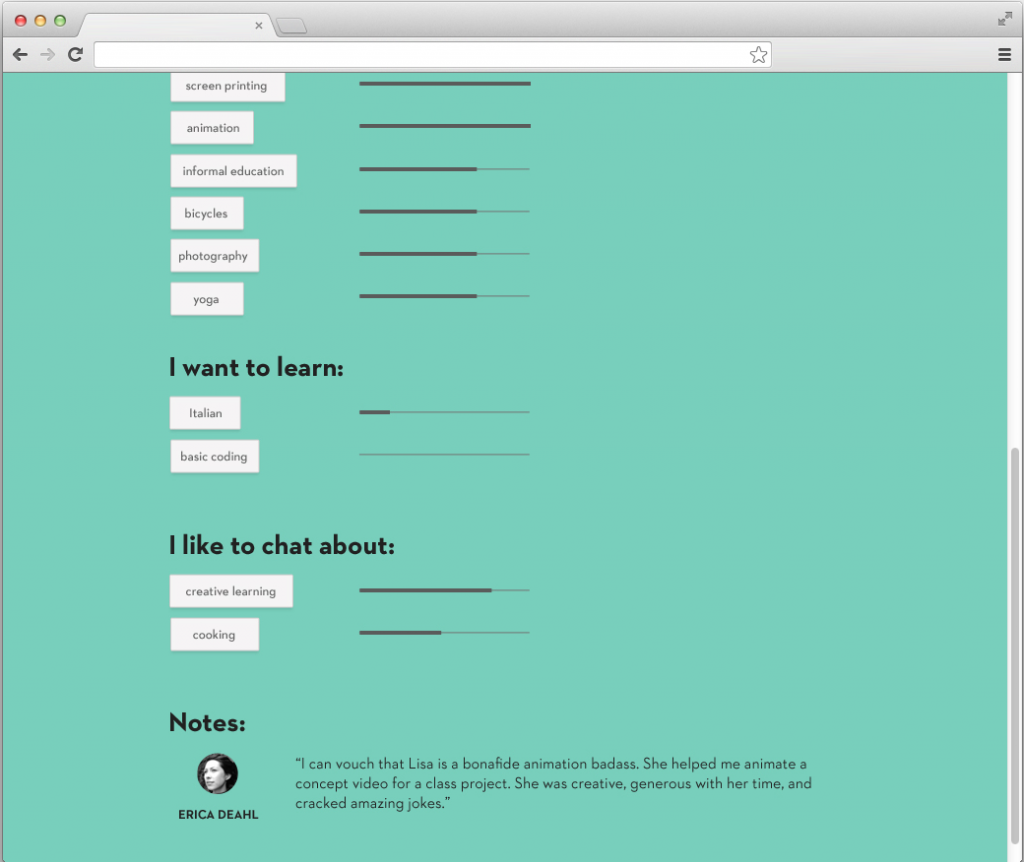

Subsequently, we launched our listserve, intending it as an asynchronous, simple, always-on channel for communication. We created the list as a Google Group, making sure that it didn’t have an MIT address so that the list’s ownership was shareable. Through some initial prompting, largely by Jason and Jessica, we invited over 30 people to the listserve, and each person made at least 1 introductory post in the first 3 weeks. Approximately an equal numbers of MIT and iHub members to pioneer the collaboration space with us. The list has a number of active but gradual conversations. The most popular has been a thread where list denizens introduce themselves to one another. The sole thread originated from the iHub side is a follow up to our video call in to their Kids’ Hacker Camp (discussed below). We hope to have more successful threads and hangout calls as a way to get to one another and build a genuine community.

Representation on Listserve by institution

Our Group’s Internal Process

Although our aim was to codesign a collaboration with iHub, our first order of business for the class was to build a shared vision for this team of four. We each came to the group on good faith that there was a shared vision to be found.

A key part of our process was reflection and self-assessment. After each interaction or design decision, we analyzed the balance of power/contribution in order to determine whether or not that step was truly grounded in our fundamental principles of inclusion and symmetry. We identified areas where we fell short and altered our approach accordingly. While these reflection discussions were time-consuming, they helped us better navigate our journey.

For example, for our second call with the iHub, we asked Jessica to gather a group so that we could see and interact with a greater variety of people. Both parties walked away wanting more, but we chalked it up to the glitchiness of the call. However, we later realized that we took up more than half the time trying to explain our vision and didn’t really leave enough time to gather feedback from them. Recognizing this led us to research conversation dynamics between cultures and genders. We made an even greater effort to solicit Kenyan voices and not make any more major decisions without a balanced dialogue.

Another valuable part of the design process was building a narrative. While this was not something we consciously realized at the beginning, we have come to feel that it is extremely important for fostering ownership over an emergent project. We were fortunate to have had documented much of our process (both for in-class presentations as well as for our own benefit), but are now considering ways to physically create this narrative (ex. blog) so that others may more easily understand the evolution of our thinking. Furthermore, the story itself adds weight to a journey and is what inspires many people to join the effort.

As a whole, our group worked extremely well together. We brought a diversity of experience and opinions to the table, but were committed to the same goal of building symmetry. We were able to complement and challenge one another.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Toward the goal of creating a symmetric collaboration with the iHub to co-design, we faced a number of challenges in- and outside of our control, and through reflection, learned a great deal from them.

Contextual Challenges

|

Challenge |

Lessons Learned |

|

Current Events. Between October and December 2014, Kenyans have been processing the events of September 13 when an attack at the Westgate shopping mall in Nairobi left over 70 people dead, hundreds wounded, and many questioning the country’s vision and capacity to address non-state terrorism and the deep socioeconomic inequalities in East Africa that might have fueled it. |

We did not address the Westgate attack with our iHub colleagues, and interesting, they did not bring it up with us either. Maybe this reflects the adolescence of this collaboration, and it would have played out differently if hublab was an established relationship at the time of the attack |

|

Asynchronous Time and Location. Nairobi is 7 (8 on DST) hours ahead of Boston. In an effort to establish interpersonal connections with our counterparts, we held Google hangouts starting between 6:00am and 9:00am in Boston. We also emailed. In the beginning, those emails were necessarily long because we didn’t have a relationship, or a commitment to a collaboration. |

Collaborations are built around a shared vision and trust. By not being co-located, it was hard to get to know each other to start this process. So much is lost when an experience or a place is translated into static words and images online. Although meeting synchronously over Google hangout improved the quality and speed at which we built interpersonal connections, we faced time constraints in terms of Boston folks needing to start their busy days, and Nairobi folks wrapping up their days to get home. We realized that a successful international collaboration needs a mix of synchronous and asynchronous modes of communication. |

|

Culture and society. Boston and Nairobi have different cultures and societies. Despite a great deal of overlap in professional skills and motivations, our differences in ideas about education, equity, gender, and religion explicitly or implicitly factored into this work. |

We attempt cultural competence in each interaction, though we have no illusions sometimes our Western-ness and African-ness will bother the other. To ensure that people raise grievances when appropriate in a way that builds cross-cultural understanding, we have to create and enforce norms around speaking up and listening in all channels of communication. |

Class

|

Challenge |

Lessons Learned |

|

No clear project or user. A key part of the design process is gathering insights, based on observation, and empathy for the experience of the end users. By nature of this collaboration, there is no clear project or end user to organize the collaboration around. Are the four of us and our Nairobi counterparts the end users? Are we co-designing for a third-party user? The answer to these questions are yes, and yes – the hublab collaboration will hopefully lead to multiple projects with multiple users. |

The trick is identifying initial viable shared projects. Based on the feedback of mentors including Juliana and our experience thus far, we believe that without shared projects that the hublab relationship will lose traction. To identify these initial shared projects, a few key people from iHub and MediaLab will have to make a plunge into this yet-to-be-defined space and be prepared to learn and fail and try again. Trust building is iterative, you have to give some to gain some. |

|

Informal vs. formal communication. We knew that building a shared understanding and trust would require informal and formal interactions. We initially ideated whole events that were structured as either formal or informal. For example, project-centered planning meetings versus demo parties with beer and music. In reality, however, the lines between formal and informal interaction are blurred. For instance, as a result of the time difference, the four of us typically logged onto Google hangout with Nairobi in the early morning from our respective couches trying to conceal greasy hair and jammies while our colleagues circled around a single laptop at iHub dressed in button down shirts. |

Having blended informal and formal communication channels is both a strength and challenge. On the one hand, these situations have tremendous potential for trust-building because you can gain a fuller impression of a person faster than if you met in a strictly formal setting. The challenge, though, is that poorly-defined social spaces can feel scary, and may prevent folks from opening up. Another potential is that people feel offput by an informal interaction because it was insensitive or experienced out of context. To manage these potential challenges, we suggested guidelines for the listserve that give contributors benefit of the doubt, and encourage listening. We have tried to model this in our posts, and in our Google Hangout conversations. |

|

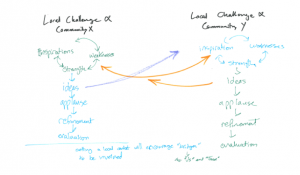

Lopsided support. Although we followed the IDEO process and reached out to iHub as our first step, the four of us started ideating for the course before we had a full picture of what is really going on in Kenya, and before they have a clear vision of the kinds of things we do at MediaLab. Added to this, both sides of the collaboration were rather unbalanced in the sense that our group is part of a course, getting a lot of support from our mentor, presenting in class and getting feedback from our peers and from IDEO, but nothing like this exists on the iHub side. When we met through Google Hangouts, this actually deterred us from good communication because the four of us are on the same page (even though it took us quite a while to get there), but the people at iHub lacked the context in which all our ideas were created. An example of this is the concept of ‘symmertorship’; they didn’t like this word at all, probably because they lack the context to understand it. |

In certain cases not being co-located can be a good thing in the sense that group thinking is more easily avoided. Also, an organic collaboration, rather than one motivated by class assignments might seem more ideal. However, co-location would allow us to know one another. If we don’t really know each other and we don’t have a clear picture of each other, how can we co-design something together if we barely have a channel of communication? As previously mentioned, we realized that before we could co-design, we need to build a relationship and we shifted our focus from building a learning platform to creating an environment in which a relationships can be established and can be nurtured. Furthermore, we came to see the course assignments and meetings with Ethan as a real asset. Juliana called this structure “lamp posts” and encouraged us to find more lamp posts to create incentives and momentum for the hublab collaboration. |

|

Chatter versus silence. In Google Hangouts and on the listserve, the voices from MIT have been louder. A great number of the comments on the listserve were prompted from the four of us, and a bulk of the posts coming from MIT. This is partly because we are motivated by the structure of this course. We also realize that Western-erns tend to fill the space in conversations, and are more likely than African to speak up in a conversation. |

We are making a concerted effort to let there be more silence, and let the conversation move slower so that it is more inclusive. By identifying a few key iHub members to move this collaboration forward, we also feel we’ll get better feedback about when to prompt, and when to listen. |

|

The relationship model. The initial hublab relationship felt like a blind dates on two levels; first our group was set up with Jessica Colaço, a contact of Ethan’s. Second, we asked Jessica to set us up with some more people at iHub, and ultimately, the two groups started working on getting more people set up on both sides. |

From the very beginning, however, the four of us wanted hublab to be a long term relationship, and we had the same feeling after talking to Jessica for the first time. The hublab relationship is therefore more like an arranged marriage; a relationship that spawns further engagement than the time allocated for a class project. It should also be noted that iHub’s was never in a class; instead they got involved in this experiment because they are motivated to build a relationship with us. Thus, opening a communication channel in which we can arrange these relationships at different levels (as a whole community, but also smaller relationships based on interest and shared visions and projects) is a top priority. |

|

Perception. We were surprised by how preconceived ideas of the other side would affect the project. For instance, we noticed that although our counterparts at iHub have a very similar skillset to ours and have been through a very similar education in similar fields, the way we see each other can be quite misleading. A concrete example of this happened during one of our interactions. iHub run a week-long hackathon for kids to build robots. We were invited to call in (via Google Hangout) at the end of the third day. They gathered around all the kids and we were chatting to them for a good hour and a half. A couple of kids were very surprised to learn than none of us have ever worked for NASA, or none of us actually work with robots. Even though this example involves kids, adult also share a perception of what happens on the other institution that might not be realistic. And obviously this happens on both sides of the collaboration. |

We were also surprised by some advice from David and Juliana of Ushahidi who said that creating a narrative of the organization as it develops is key; the narrative is a shared adaptive vision and the inspiration for new members to join. Misperceptions can make for great stories while developing that shared narrative. The trick is finding ways to call out the misperceptions when they occur, and finding common ground through them. We might have crushed some kids’ hearts when by saying we don’t work for NASA or play with robots, but we plan to use these stories to share smiles and move the relationship along with iHub. |

Next Steps

hublab:

We consider this process only a fraction of the way completed. We plan to continue building this relationship between MIT and the iHub and are in the process of identifying a core group of champions who have the time and passion to meet regularly. We have already had some individuals step up to be part of this group (3 from Kenya, 1 from MIT), and will continue reaching out for more. To stay true to our guiding principle, we want to renew our commitment to symmetry by ensuring this group co-designs the listserv space using a shared vision that they create together. We also hope that the possibility of co-location via a trip to Kenya or vice versa may be able to happen in the near future to cement this partnership.

Now that we have created a space, we would like to begin offering opportunities for interaction, possibly including a demo party, project karaoke, and/or unhangout. We are also considering the possibility of bringing a third party into the fold; in creating something together for a third party, the members of hublab. With Dana moving to Rwanda early next year, we could even pull off a Boston-Nairobi-Kigali connection!

Finally, we think it would be valuable to partner this course with a course in Kenya that has like goals and a similar timeline. It does not have to be the same exact course, but one that shares our end goal of researching/creating an effective online learning collaboration. We feel that such a shared structure and commitment obligations on the part of all participants would infuse the relationship with a more natural symmetry that comes out of shared goals.

Portraits of Success

Underlying all good relationships, whether they are arranged, spring from a blind date, or develop organically, is a friendship. Friendship is not something measurable (like a platform or a product), but rather an intangible bond that exists between people. There is no set formula to build it and no time frame that dictates when it happens. We cannot say when it is “complete” or “enough” because just like relationships, a successful friendships feels different for everyone.

Luckily, people do not have to be co-located to share a passion or form a friendship. There is a wide range of ways the listserv can be considered “successful,” all of which can be considered worthy in their own right. Here we lay out some of the main success scenarios:

-

Organic Shared Projects. These are projects that spring from conversation, not merely from one side or the other soliciting members to join a pre-existing team/project. Not to say that’s a bad thing, but a more telling metric would be co-ideated and co-designed projects that are the outcomes of a collaboration.

-

Relationships based on mutual interest. These relationships can be either 1-to-1 or 1-to-many, but our vision is that they are pockets of people who connect because of similar interests. We are already seeing a little of this kind of activity come out of the listserv, but it’s at the very beginning stages.

-

Trigger free. This means members will not have to be “forced” or “reminded” to use the space (kind of like we were for this class), but will naturally think of it as a space they can come to for sharing resources, feedback, and insight.

-

Core Group of Champions. While we are planning to stay involved, we ultimately want this collaboration to be something the four of us can walk away from. We believe that having a core group of champions on both sides of the ocean who are committed to keeping the group going is essential to ensure the partnership grows. We already have three individuals in Kenya (Jessica, Wachira, and Elizabeth) as well as one in the Media Lab (Chelsea Barabas) who are interested, and have set up a meeting next week to discuss how we would like to move forward.

-

Co-Learning and Symmentorship. This, as we all remember, was the point of this class! We see this happening through co-teaching of skills and exposure to one another’s work that leads to co-learning and fosters our original theory of symmentorship as a pathway to mastery.

Overall, with the creation of this listserve, we sought to become like the four professors of this class by gathering interested and capable people into a common space to fuse their passions and co-create something larger than the sum of the parts.

Beyond MAS.S70

Through this experience of co-design and relationship building, we each take back lessons and reflections to apply in our own domains.

Laura’s Reflections

This is what I wrote when I applied for a spot in this class

“Having taught/lived in a very remote region of Honduras for 3 years, I’m interested in ways of enhancing learning experiences where schools have had little previous access to any sort of technology (or electricity, for that matter). I’m fascinated with devices/programs that use an individual-paced adaptive learning platform. However, I believe that these emerging platforms must be designed in conjunction with local pedagogy and designed specifically for local learning contexts. I’m also interesting in creating educational curriculums that look ahead to develop the 21st-century skills necessary for students to be productive, global citizens.”

I have always framed my areas of research around two things: (1) using technology to increase access to quality education for students with limited resources, and (2) promoting 21st century skills that develop students into lifelong learners and responsible global citizens. This process has altered the way I see the first. I now understand the complexities that come with trying to increase “access” and “quality” of education by merely enhancing technology. It takes more than a well-built platform to form meaningful relationships across distance; it takes time, commitment, and ownership. Technology is not a replacement for co-location. I am increasingly fascinated by what is lost in the fiber-optic cables that carry virtual conversations between people. Because the personalities of individuals and goals of each relationship is unique, it’s hard to design spaces in which people can find mentors and form meaningful connections. Moving forward, I plan to rethink technology’s role in my definition of “access.”

One of the things that I love to do is write and tell stories. I have a natural talent for finding the right words, using digital media, creating images, and generating pop-culture references to communicate with an audience. Yet, I think of storytelling as a fun side project. Juliana’s view that creating a narrative is an essential part of the collaboration process has allowed me to rethink the role of storytelling in my work. Telling stories is a way to build empathy that lays the foundation for symmetrical relationships. Moving forward, I think I have to stop discrediting it “fun” and start thinking about how it can be used to foster trust, inspiration, and meaning for others.

José’s Reflections

Although I have always found that co-design is implicit in my work with students in open source projects (they always co-design a solution with a mentor), I find the idea of merging co-design and symmetry very appealing and intriguing. I see the relations established in apprenticeship settings happening at multiple levels in which anyone, at a given time, is always a peer. A master to master relationship is a relationship of peers, and it’s only through acceptance by your peer network that you become one of them. This happens at all levels (journeyman and apprentice).

But to achieve symmetry in a relationship, the relationship itself cannot be unbalanced (members have to be peers). Since the beginning of this project, Symmetry has been bugging me big time.

I am somehow fixated with the symmetry of symmetry (I know…). If the relationship is unbalanced (eg. master to journeyman) then the interaction cannot be symmetric. We discussed a few times scenarios in which, for instance, one person would benefit from learning a new skill, and the facilitator would benefit from the interaction with the learner. What’s symmetric about that though? I’m not implying that what each side learns has to be quantified and be made equal, but if both sides do not benefit in the same way, then there is no symmetry.

I can see symmetry in a study group; I also see symmetry in our group, four rather different people joining forces to solve a problem and learning in the process. I need to think more about how this can be applied to open source projects; it won’t work just by putting 2 to 4 people together, but they will also need to be given the tools to go through the process we went through. I am teaching a software engineering class in the Spring term and I have to get some of these techniques in this class folded in within the Agile methodologies labs, and make students apply them in their designs.

Another takeaway from this class is the different ideas about group formation and about group and power dynamics. It was very interesting to see the different interactions within our group from the design, development, teaching, and entrepreneurial fronts. We perceived certain topics or ideas in radically different ways, but we managed to make that a good thing.

I have also always been fascinated by the importance that language plays in community interactions, and how it can play an important role in identity and belonging to a group. A good example of that is Symmentorship; you’ll have no idea what I am talking about if you are a Muggle.

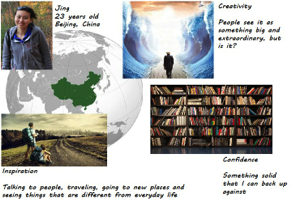

Dana’s Reflections

This course introduced me to education and design concepts that brought tremendous insight to my work as a research mentor, and gave me a ton of opportunities to improve my own teamwork skills. Furthermore, I used IDEO design tools to help flesh out a grant proposal during the course, and I will likely use them again soon as I co-design a research mentorship program for clinical researchers in Rwanda in my new job starting in January.

The grant proposal is something that I’ve been thinking about, and trying to articulate, for almost two years. It’s why I joined this course! The concept is to transform the scientific literature from just a research repository into a learning platform by integrating video tutorials and other multimedia into scientific articles. In the grant, I organized the deliverables around user desirability, technical feasibility, and business sustainability, a design framework posed by IDEO. When the application asked, “What is the primary question of university-level [Harvard] interest that you are addressing in your proposal?”, I responded with: “How might we leverage research as a teaching and learning opportunity?” Another IDEO tool.

Learning to phrase “how might we” questions has allowed me to participate in ideation conversations in completely new ways and it opened a door toward finding creative confidence in myself. Before learning “how might we”, I would have started a thought with “how about” or “what if”. The latter two phrases lead to proposals, which, in a collaboration space can come across as bossy or deterministic. It also leaves the person making proposals vulnerable to flat “yes” or “no” responses; and “no, I don’t like that idea” does not lead to creative confidence. “How might we” is an invitation. It broadens rather than narrows the conversation. And this simple phrase has allowed me to participate in groups in more creative, productive ways.

The very concept of creative confidence was new to me at the start of the course; this and a number of other concepts have been immensely helpful.

When Patty made the distinction between “just in case” versus “just in time” learning in her presentation, for example, the loose pile of ideas in my head around adult learning and learning as a busy professional, started to snap into place.

As a geographer and public health person, I don’t have formal training in education theory. Through my work on a team of research mentors at Harvard Medical School, however, I have a lot of impressions of what successful mentorship and training looks like for overworked, passionate clinicians, community health workers, health facility managers, and program planners in low-resource settings. These learners don’t apply concepts with much success after generalized trainings. For them, there is often a patient or mini-crisis that is more important than a scheduled lecture or meeting in the middle of the day, and so attendance of regularly scheduled events is poor. The most successful examples of learning and mentorship that I have witnessed (and experienced) involve mentors who are responsive to questions as they arise, who provide personalized support, and who teach through example. Although “just in time” learning can by non-personalized, the distinction between “just in time” and “just in case” is leading me to consider minimizing lectures, and instead assembling example work and personalized assignments to help mentees work through their own research projects.

Jason’s Reflections

This semester, I’ve been near-constantly under the weather and miserable just about constantly. Virus, sinus infection, back pain – I’ve been a physical disaster. The thing about pain is that you really can’t focus very well and everything seems that much harder. Oh, and I’ve been in a statistics class that crams a year of material and effort into a single semester. So why am I so happy about also facing one of the most intellectually and emotionally draining challenges I’ve faced as a graduate student at MIT?

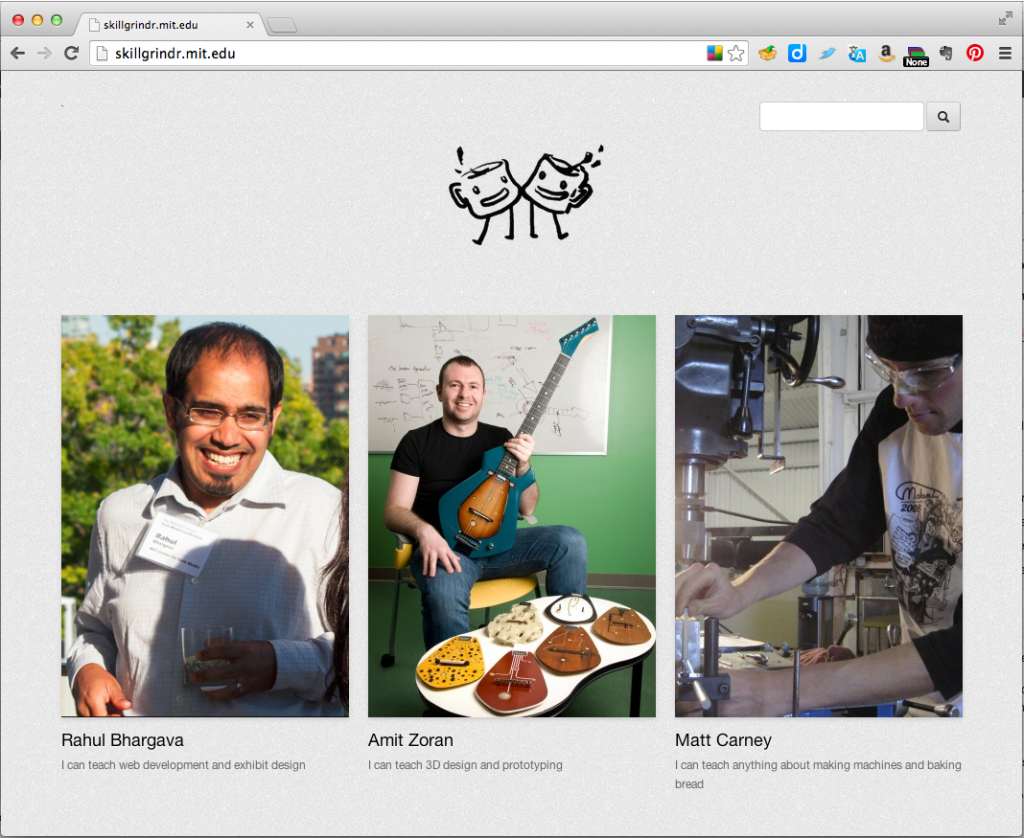

A) The Project: Staring at the board on the team creation day, looking for where to put my PostIt notes, I was surprised to find myself placing one on the space for developing countries/symmetry. I’d been actively thinking about how to make MOOCs a better place to learn and teach (especially if they’re seemingly going to exist anyway), and have been working on getting skillsharing going in the Media Lab via the Festival of Learning and Studcom for 5 semesters now. But since my Masters work, I’ve been really compelled by how power dynamics and identity issues are in some ways inherent to the interpersonal dynamics that occur when people learn from and with each other. Ethan’s positioning of the missionary stance and the challenge of teaching someone something while seeing them as an equal, attempting to hold in mind the value that person contributes and the many things you may wish to learn from them, avoiding the opportunity to elevate yourself, was unshakable. So I picked a new adventure, and I am entirely changed and compelled.

After all of our work in the IDEO process, grinding away in the ideation mines, it was really pleasing that in the face of such daunting challenges – mutually coaching one another and building shared culture across the Atlantic with no physical co-presence – we kept coming back to the really human issues inherent to the project. We should share food! And music! And T-shirts! And what if there was daycare…? We looked at the challenge before us from the class and started ideating the platform, already factoring our experiences from the Tufts Social List and Awesome@Media into our thinking and Dana and Laura did a particularly wonderful job drawing out plans for what our platform could do. But as we talked, the ghosts of unused platforms wafted into the room. The idea of showing up to meet our Kenyan friends with an aircraft carrier of a platform already built moved us to silence. So what if we just started a mailing list? The absurdity was of course wonderful, but this absurdity was amplified by the fact that it just kind of seemed right.

At this point, we have e-met some wonderful Kenyans, excited some really great people from around the Media Lab about working with Kenyans, and gotten great feedback and respect from luminaries like Philipp Schmidt, Mitchel Resnick, and of course Ethan Zuckerman. The mailing list will live on, with help from all of us, and not just collect a grade before hitting the recycling bin. And in my fondest dreams, it exists beyond any of our individual participations.

B) The Process: Honestly, I tried to remember or find documentation of my AEIOUs, and I couldn’t. I’m pretty sure that all I cared about were symmetrical Interactions. It was really great to participate in IDEO’s process and do the collective, exhaustive mining that allowed us to find the gems of what we really cared about as a team. It was really useful to have Laura around as a local expert as well, introducing further models or providing nuance and clarity when IDEOs tools weren’t quite getting the job done. But as fun as that capital-P-process was, the process of grinding out the steps necessary to make things happen were immensely satisfying to me – getting 6 to 8AM Google Hangouts going, doing the shoe leather work around the Media Lab that led to Erhardt, Alexis, Nathan, and highly-in-demand Scratch expert Abdulrahman to show up for the the Kids’ Hacker Camp call, and maintaining the traffic on the list (perhaps too actively for a time). I enjoyed coming to understand the narrowest amount of what sorts of challenges and victories a place like the iHub has, and, despite my general exhaustion in the face of meeting strangers, seeing others get deeply excited at the process at making new transatlantic friends on both sides was extremely inspiring. All we did was open a window, and people were ready to wave over the hedges.

Whether or not this sort of thing is sustainable without ever meeting one another in person is another question. We tried a number of activities to get things going on the list, and only the Hacker Camp call felt like an unambiguous win. It’s been exciting to think through the design features and feedback loops of anarchist organizing techniques and how to make them land online. The answer hasn’t full emerged yet, but I hope to continue meditating on that hard problem. And even as I despair a bit, we were able to hear from Juliana Rotich and David Kobia that, yeah, these things are hard and a grind and they take time. We were on the right track, but the wrong timeline. And hey, Elizabeth wants to try project karaoke sometime!

C) The Team: We agreed to make a mailing list together. The importance and value of the thinking, care, and risk-taking that went into that decision can’t be overstated. It’s not every group project with high-achieving types in demanding environments that will agree to jump over the waterfall together even though they know it’s the right thing to do. I have so many fun memories from this process, and really, once you call Kenya at 6AM with people while you’re in your jammies, you’re kind of family. This was a remarkable group to work with and I was struck in reflection by how necessary all of our diverse skill sets, networks, and personalities were to getting this thing to fly. I think we found this in part because we were great at seeing and utilizing resources, and respectful without being afraid to speak our minds. What more can you ask?